Persistent Dyspnea Despite Maximal Medical Therapy in COPD

Reviewed By Allergy, Immunology & Inflammation Assembly

Submitted by

Brian P. Mieczkowski, DO

Fellow

Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

The Ohio State University Medical Center

Columbus, Ohio

Michael E. Ezzie, MD

Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine

Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

The Ohio State University Medical Center

Columbus, Ohio

Submit your comments to the author(s).

History

A 64-year-old woman with a history of smoking presented with progressive shortness of breath with exertion. The patient smoked one to two packs of cigarettes per day for forty-two years and quit smoking one year ago. She had increasing dyspnea on exertion over the past few years that accelerated over the last year. She reported she could now only walk short distances before sitting down to catch her breath. Her family doctor started her on bronchodilators a few years ago. She had improvement at the time, but now feels very limited. She had several episodes of increased dyspnea, wheezing, and productive cough over the past two years. These exacerbations were treated as an outpatient with oral corticosteroids and antibiotics. Two years ago, she participated in a four week course of pulmonary rehab which resulted in improvement in her dyspnea. She denied chest pain or palpitations with breathing symptoms. She reported no shortness of breath at rest, except when talking for more than a few minutes. She had no emergency department visits and had not required mechanical ventilator support for breathing. She had no nocturnal symptoms of wheezing or shortness of breath, but did have occasional wheezing during the day along with a dry cough. The patient was interested in discussing additional therapies for her lung disease.

Her past medical history was significant for smoking, depression, arthritis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin on the leg that was removed.

Her current medications included amlodipine, sertraline, aspirin, tiotropium, albuterol, salmeterol/fluticasone, and simvastatin.

The patient reported that her father had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). There was no other family history of lung disease.

The patient had been married for forty-five years and had two children. She was a former smoker of one to two packs per day for forty-two years. She denied alcohol or drug use. She reported no significant occupational exposures.

A review of systems was pertinent for fatigue and occasional heartburn.

Physical Exam

On examination, the patient’s weight was 118 pounds with a body mass index (BMI) of 20.3. Her blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg with a pulse of 96 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation was 91% breathing ambient air. Her general appearance was thin, and notable for a pleasant female who was alert and oriented in no acute distress.Her oropharynx was clear without exudate and neck exam revealed no lymphadenopathy. Her lung exam had diminished breath sounds bilaterally with comfortable respirations and an appreciably long expiratory phase. No wheezes, rhonchi or rales were noted. Cardiac exam was normal rate with a regular rhythm. Abdomen was thin, soft and nontender and extremities showed no evidence of clubbing or edema.

Diagnostic studies

Pulmonary Function Tests:

| Forced Expiratory Volume in one second (FEV1): |

0.84 L (34% predicted) |

| Forced Vital Capacity (FVC): |

2.46 L (56% predicted) |

| FEV1/FVC: |

0.34 |

| Total lung capacity (TLC): |

138% of predicted |

| Residual volume (RV): |

227% of predicted |

| Diffusing Capacity of Carbon Monoxide (DLCO): |

31% of predicted |

6-minute walk distance: She walked 900 feet and desaturated to 91%.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: Her power output was 20 watts.

Arterial blood gas: Baseline measurement of pCO2 was 37 and pO2 was 72. The carboxyhemoglobin level was 0.

Figures

Figure 1.1: Posterior-Anterior and Lateral Chest Radiograph - Demonstrating hyperinflated lungs with emphysema

Figure 1.2: High Resolution Computed Tomography (CT) of the Chest - Demonstrating severe changes of upper lobe predominant pulmonary emphysema.

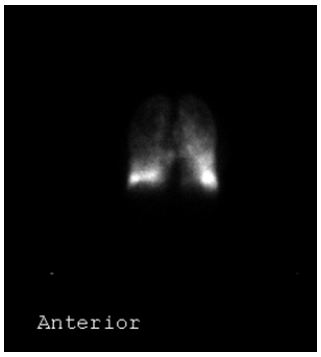

Figure 1.3: Lung Perfusion Scan – Demonstrating her right upper lobe with 3.6% of total perfusion, her left upper lobe with 5% of total perfusion, her right middle lobe 13.6% of the total, her right lower lobe 26.3% of the total, and her left lower lobe 25.8% with left middle area 25.7%.

Correct Answer: D

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is defined as airflow limitation that is not fully reversible and is progressive with an associated abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious stimuli (1). COPD is diagnosed by spirometry, with a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of less than 0.7 and is classified by the degree of loss of FEV1. The leading cause of COPD in the United States is cigarette smoking and the number of women dying from COPD is now equal to or surpassing the number of men (2).

There is an increased understanding of gender differences in COPD development and progression. Women tend to develop COPD at an earlier age and generally have less pack-years of smoking compared to men with similar FEV1 values (3). Chest CT scans of female patients have less evidence of emphysema and histological examinations demonstrate thicker airways and narrower lumens when compared to men with equivalent levels of obstruction (4). Even with this phenotypic difference, there has been no data to suggest that women have a greater response to bronchodilators.

Given the increased risk of smoking-induced lung impairment, women may benefit from smoking cessation more than men. The Lung Health Study found women had 2.5 times greater percentage improvement in FEV1 compared to men one year after smoking cessation (5).

Correct Answer: A

Multiple indices have been developed to predict outcomes in COPD. The BODE index described additional parameters to improve upon the FEV1-based mortality prediction in patients with COPD. It has also been validated to predict hospitalizations. The BODE index includes: BMI, degree of obstruction, symptoms of dyspnea, and exercise tolerance based on a six minute walk test (6). The DOSE index, in addition to functional status, includes the frequency of exacerbation in its prediction for hospitalization, respiratory failure and subsequent exacerbations over the next year. The components include dyspnea symptoms, degree of obstruction, smoking status, and exacerbation frequency(7). The ADO index was designed to simplify and improve the all-cause mortality prediction of the BODE index and found age to be an important factor. It includes age, dyspnea symptoms, and degree of obstruction (8). The COPD prognostic index (CPI) is another index that uses exacerbation history to help predict future exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality. The CPI was developed from pooled data of 12 randomized controlled trials. The components include age, gender, degree of obstruction, quality of life, BMI, frequency of exacerbations, and history of cardiovascular disease (9).

Correct Answer: E

The patient does have moderately low oxygen levels on her six minute walk test to 91%, but there is no data to suggest she would have a 5 year mortality benefit from supplement oxygen. Patients with very low oxygen levels at rest (paO2 less than 55 mmHg) had improved survival in early studies of home oxygen use (10, 11). The ongoing Long-term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT) (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00692198) is assessing the effect of supplement oxygen in COPD patients with moderate hypoxemia.

The TORCH trial evaluated the effectiveness of a long acting beta agonist (LABA) with and without an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). The combination was most effective at improving lung function and quality of life as well as decreasing the time to the next exacerbation (12). The study did not however, demonstrate a statistically significant mortality benefit in regard to death from COPD with the use of a LABA with ICS. The INSPIRE trial reported that both tiotropium and a LABA with ICS were equally effective at decreasing the annual exacerbation rate. Similar to other trials with inhaled corticosteroids, INSPIRE did show an increased risk of pneumonia in the ICS treatment group (13). The GOLD guidelines currently suggest adding an ICS in symptomatic patients with an FEV1 less than 50% who also have frequent exacerbations (1). Based on retrospective data showing ipratropium may increase adverse cardiac events, there was a concern with a class effect with tiotropium. The UPLIFT trial found fewer cardiac events and a decreased cardiac mortality in the tiotropium treatment group (14). Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve exercise tolerance, quality of life, and decrease healthcare utilization, but studies have not been powered to assess the effect on mortality (15).

Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) has been shown to improve dyspnea scores, dead space ventilation, exercise tolerance, and quality of life. In select patients, including our patient, LVRS may improve long-term mortality as well (16-18).

Correct Answer: C

Lung Volume Reduction Surgery (LVRS) is done by performing a wedge resection of emphysematous lung tissue in select patients with COPD that are poorly controlled despite maximal medical therapy. LVRS is thought to improve a patient’s functional status by increasing the elastic recoil and expiratory airflow by restoring the outward circumferential pull on small airways. In addition, it is thought to help improve the strength and efficiency of the diaphragm by decreasing the radius of its curvature.

The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) showed that LVRS improved dyspnea symptom scoring, minute ventilation with exercise, and maximal exercise capacity (16). A group of patients with an FEV1 less than 20% predicted and a diffusion capacity of less than 20% predicted were found to have a 30-day mortality rate of 16%. These patients were termed high risk and were eliminated from further analysis (19). Among the remaining non-high risk patients, mortality at 30-days was increased (2.2% in the LVRS group versus 0.2% in the maximal medical therapy group), but long term mortality at two years was similar. A subgroup analysis divided patients into groups based on location of emphysema and high versus low exercise capacity defined by a cut off of 40 watts in men and 25 watts in women. At 24 months, the subgroup of upper lobe predominate emphysema and low exercise capacity had improved survival, while the subgroup of patients with homogeneous emphysema and a high exercise tolerance had decreased survival. The other two groups did not show survival benefit or an increased risk of death.

Correct Answer: E

Patients that have COPD with severe obstruction and upper lobe predominate emphysema with poor control despite maximal medical therapy can be considered for LVRS. To better stratify which patients will benefit from LVRS, further evaluation of their physiology and functional status is needed. This evaluation should include a full set of pulmonary function testing, a six minute walk, a cardiopulmonary exercise test, an ABG, and an echocardiogram. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require that a patient have an FEV1 less than 45% predicted and if over 75 years of age, the FEV1 must be greater than 15% predicted. If the FEV1 is less than 20% predicted, the DLCO must be greater than 20% predicted. The patient must also be stable on less than 20 mg of prednisone a day. A minimal total lung capacity of 100% predicted and a residual volume of 150% predicted are needed to qualify. There is evidence that a higher RV to TLC ratio yields greater improvement in post-operative FVC. Participation in a minimal 6-week pre-operative pulmonary rehabilitation program is required and a post-rehabilitation six minute walk of greater than 140 meters is needed to be considered for LVRS. An arterial partial pressure of oxygen of 45 mmHg or greater and a partial pressure of carbon dioxide less than 60 mmHg are also requirements from CMS. If a patient has an ejection fraction of less than 45% then evaluation and approval by a cardiologist is required. Other factors that may exclude a patient from LVRS include: active smoking, severe cachexia or obesity, comorbid lung or pulmonary vascular disease, and prior thoracic surgery.

Correct Answer: A

The most common post-operative complications from LVRS are persistent air leaks, cardiac arrhythmias, pneumonia, and respiratory failure requiring sustained mechanical ventilation or re-intubation. NETT found that air leaks occurred in 90% of patients with a median duration of seven days and 12% of patients had an air leak for greater than thirty days. Cardiac arrhythmias were the next most common complication with 23% of patients developing an arrhythmia within the first thirty days. Pneumonia develops in approximately 18% of patients in the post-operative period. Renal failure is not a common complication after LVRS surgery (16). A recent review of patients that underwent LVRS based on the NETT criteria had prolonged air leak (greater than 7 days) as the most common complication, occurring in 43% of patients (17). Persistent air leaks often lead to a protracted time that the patient needs a chest tube, longer hospitalizations, and may require further surgical intervention to repair the bronchopleural fistula.

References

- Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: GOLD Executive Summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532-555.

- Minino AM, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Death in the United States, 2007. NCHS Data Brief 2009:1-8.

- Chapman KR. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Are Women More Susceptible Than Men? Clin Chest Med 2004;25:331-341.

- Dransfield MT, Washko GR, Foreman MG, Estepar RS, Reilly J, Bailey WC. Gender Differences in the Severity of CT Emphysema in COPD. Chest 2007;132:464-470.

- Connett JE, Murray RP, Buist AS, Wise RA, Bailey WC, Lindgren PG, Owens GR. Changes in Smoking Status Affect Women More Than Men: Results of the Lung Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:973-979.

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes dO, Mendez RA, Pinto P, V, Cabral HJ. The Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise Capacity Index in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005-1012.

- Jones RC, Donaldson GC, Chavannes NH, Kida K, Dickson-Spillmann M, Harding S, Wedzicha JA, Price D, Hyland ME. Derivation and Validation of a Composite Index of Severity in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: the DOSE Index. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:1189-1195.

- Puhan MA, Garcia-Aymerich J, Frey M, ter Riet G, Anto JM, Agusti AG, Gomez FP, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Moons KG, Kessels AG, et al. Expansion of the Prognostic Assessment of Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: the Updated BODE Index and the ADO Index. Lancet 2009;374:704-711.

- Briggs A, Spencer M, Wang H, Mannino D, Sin DD. Development and Validation of a Prognostic Index for Health Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:71-79.

- Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Continuous or Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy in Hypoxemic Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: a Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med 1980;93:391-398.

- Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Long Term Domiciliary Oxygen Therapy in Chronic Hypoxic Cor Pulmonale Complicating Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema. Lancet 1981;1:681-686.

- Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, Yates JC, Vestbo J. Salmeterol and Fluticasone Propionate and Survival in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775-789.

- Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA. The Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations by Salmeterol/Fluticasone Propionate or Tiotropium Bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:19-26.

- Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, Decramer M. A 4-Year Trial of Tiotropium in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543-1554.

- Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD003793.

- Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Weinmann G, Wood DE. A Randomized Trial Comparing Lung-Volume-Reduction Surgery With Medical Therapy for Severe Emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059-2073.

- Ginsburg ME, Thomashow BM, Yip CK, DiMango AM, Maxfield RA, Bartels MN, Jellen P, Bulman WA, Lederer D, Brogan FL, et al. Lung Volume Reduction Surgery Using the NETT Selection Criteria. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1556-1560.

- Hardoff R, Shitrit D, Tamir A, Steinmetz AP, Krausz Y, Kramer MR. Short- and Long-Term Outcome of Lung Volume Reduction Surgery. The Predictive Value of the Preoperative Clinical Status and Lung Scintigraphy. Respir Med 2006;100:1041-1049.

- National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Patients at High Risk of Death After Lung-Volume-Reduction Surgery. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1075-1083.