Playing with Carts

Louella Amos, MD

Associate Professor of Pediatrics

Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine

Medical College of Wisconsin

Children’s Wisconsin

Case:

A 17-year-old cognitively normal female with past medical history of depression and anxiety presented to the ER after several days of “not feeling great.” She reported several months of fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea but no weight loss. She had undergone outpatient GI consultation including an EGD which was suggestive of eosinophilic esophagitis, but there was no improvement in her GI symptoms with swallowed budesonide. On the day of admission, she became severely dyspneic and hypoxemic requiring 30LPM of HFNC. Labs revealed a WBC of 18.7 with 94% neutrophils, procalcitonin of 0.26 and normal AST and ALT.

Question:

What is the likely diagnosis?

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Hydrocarbon ingestion

- E-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury

D. E-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury

Discussion:

-

Aspiration pneumonitis is not correct because she has no neurologic deficit that would result in risk for aspiration. She also has a several month history of GI symptoms, which would cause more chronic respiratory symptoms rather than her acute presentation. Finally, the opacities on chest imaging are in the dependent regions of the lung rather than the upper lobes, which would be seen in the classic case of alcohol intoxication resulting in emesis and aspiration.

-

Hallmark findings in sarcoidosis on chest imaging include bilateral hilar adenopathy and perilymphatic nodules, with parenchymal changes in the mid to upper lungs. Our patient’s chest CT revealed ground glass opacities in the dependent regions of both lungs with areas of subpleural sparing.

-

Hydrocarbon ingestion most commonly occurs in children younger than age 5 and is due to accidental ingestion and aspiration. Chest radiographs may reveal small patchy densities at first with coalescence of the opacities with clinical progression. Emphysema and pneumathoraces may develop.

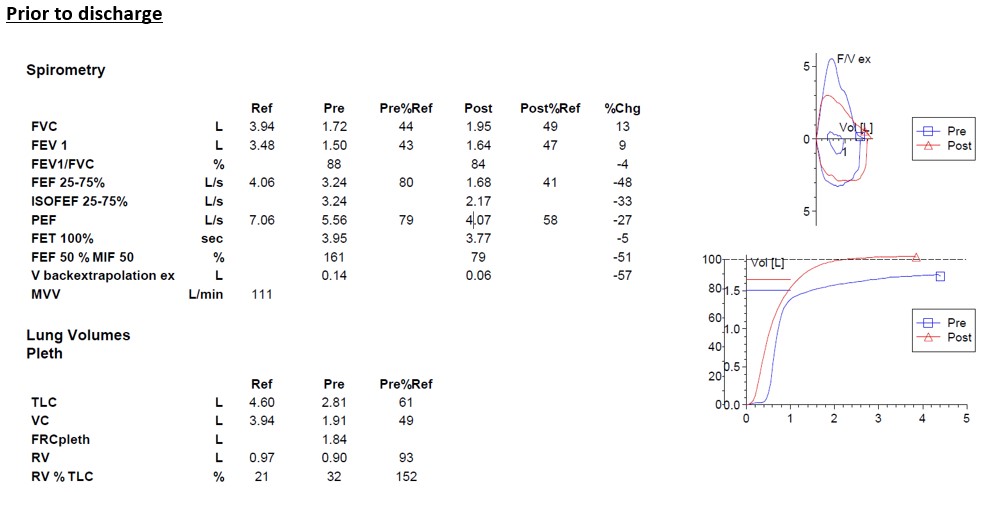

Prior to intubation, our patient reported vaping for 1 year and “using” marijuana. Her e-cigarette products were submitted which included THC cartridges or “carts” and e-liquid containing nicotine. She ultimately required mechanical ventilation with neuromuscular blockade to adequately oxygenate and ventilate her. She received 1 gram IV methylprednisolone daily x 3 days and was extubated 2 days after completing these pulse steroids. Pulse steroids were followed by daily enteral steroids which were weaned over the next 2-3 weeks as an outpatient. Spirometry was obtained prior to discharge which is shown below. She required supplemental oxygen upon discharge due to an abnormal 6-minute walk test.

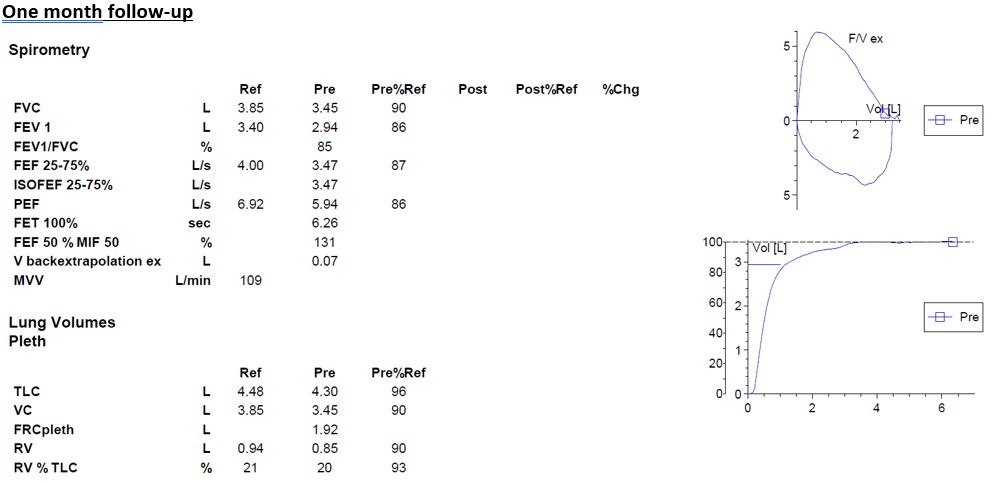

At her 1-month follow-up visit, she reported no longer vaping, her GI symptoms had resolved, and she no longer needed oxygen. Repeat imaging and 6-month follow-up was recommended but never completed because of the national shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Presenting symptoms of EVALI are often subacute developing over 2-4 weeks prior to presentation. These symptoms include cough, dyspnea, chest pain, nausea, anorexia, diarrhea and fever. In general, several months of constitutional symptoms (e.g. night sweats and fatigue) and GI symptoms precede the development of respiratory complaints. They can have significant weight loss (20-40 lbs) during this time period.

Children with suspected EVALI should undergo chest imaging, often beginning with a chest x-ray. Bilateral diffuse opacities with lower lobe predominance is consistent with EVALI. Many children may have normal chest x-rays on first presentation. If suspicion for EVALI is high, they should undergo a chest computed tomography scan which often shows ground glass opacities in the dependent regions of the lungs with sub-pleural sparing.

EVALI has been diagnosed in children who vape products containing nicotine and/or THC; however, the THC cartridges or “carts” seem to be more strongly associated with the development of EVALI. Vitamin E acetate, a common diluent of the THC oil in the cartridges, has been implicated as the cause of the lung injury. The mainstay of EVALI treatment is the initiation of systemic corticosteroids. To date, no guidelines exist for the appropriate dosing and duration of therapy. If children do not meet criteria for inpatient admission, the initiation of oral corticosteroids may be appropriate if workup for other conditions has been completed.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the vaping epidemic in children. Adolescents have been using e-cigarettes to manage their anxiety and stress even before the onset of the pandemic. Because of increased restrictions and difficulty purchasing e-cigarettes, teens in our adolescent clinics report sharing devices, which promotes the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Adolescents who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 are more likely than younger children to present with the classic COVID-19 symptoms which mimic EVALI. For this reason, screening for vaping in pediatrics is essential now more than ever.

References

-

Rao DR, Maple KL, Dettori A, Afolabi F, Francis JKR, Artunduaga M, Lieu TJ, Aldy K, Cao DJ, Hsu S, Feng SY, Mittal V. Clinical Features of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury in Teenagers. Pediatrics. 2020 Jul;146(1):e20194104. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4104. Epub 2020 May 11. PMID: 32393606.

-

Artunduaga M, Rao D, Friedman J, Kwon JK, Pfeifer CM, Dettori A, Winant AJ, Lee EY. Pediatric Chest Radiographic and CT Findings of Electronic Cigarette or Vaping Product Use-associated Lung Injury (EVALI). Radiology. 2020 May;295(2):430-438. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192778. Epub 2020 Mar 3. PMID: 32125258.

-

Jatlaoui TC, Wiltz JL, Kabbani S, Siegel DA, Koppaka R, Montandon M, Adkins SH, Weissman DN, Koumans EH, O'Hegarty M, O'Sullivan MC, Ritchey MD, Chatham-Stephens K, Kiernan EA, Layer M, Reagan-Steiner S, Legha JK, Shealy K, King BA, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Rose DA, Delaney LJ, Briss P, Evans ME; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group. Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers for Managing Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury - United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 22;68(46):1081-1086. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846e2. PMID: 31751322; PMCID: PMC6871902.